CD Linernotes von Manfred Papst, NZZ am Sonntag

Das Vieleck wird zum Kreis

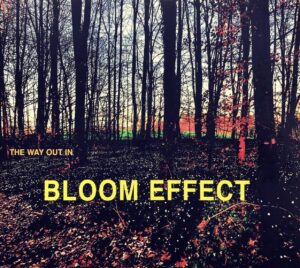

Der Rabe isst Pasta. Stillvergnügt, zielstrebig, ganz bei sich. Mit trippelndem Schritt rückt er ins Bild. Verwundert geraten wir in seine Welt und vergessen die Zeit. Später werden wir gewahr, dass die Entführung nur achteinhalb Minuten gedauert hat. Was ist passiert? Wir sind eingetaucht in die magische Musik des Quartetts «Bloom-Effect», genauer: ins erste Stück des Albums «The Way Out In». «Rabe isst Pasta»: Der Titel, der über einem surrealistischen Bild stehen könnte, bringt das musikalische Geschehen auf den Punkt.

Gitarrist Franz Hellmüller und Saxofonist Jochen Baldes haben so lange Ideen miteinander ausgetauscht. bis daraus eine kompositorische Einheit wurde, welche sie dann in die Bandprobe mitbrachten. Dort wurden die Kompositionen im kollektiven kreativen Prozess weiter entwickelt zu einem stimmigen Bogen, dessen Leichtigkeit verbirgt, wie komplex es ist. Die anmutige Melodielinie des ersten Themas wird im Spiel von Saxofon und Gitarre so aufgefächert, dass man im ersten Moment glaubt, mehrere Bläser zu hören. Der exakt gesetzte Part öffnet sich zu improvisierten Teilen im Idiom des klassischen Modern Jazz; Hellmüller und Baldes improvisieren in ungeraden Metren, als wäre das die einfachste Sache der Welt. Patrick Sommer am Bass und Tony Renold am Schlagzeug tun nicht nur, was man sich von einer pulsierenden Rhythmusgruppe wünscht; mit subtilem, poetischem Spiel bringen sie den Klangteppich regelrecht zum Fliegen.

Schon das erste Stück auf «The Way Out In» zeigt exemplarisch, worum es der Band in diesem Projekt geht: um eine hybride Form von Jazz, die von der Spannung zwischen kompositorischem Raffinement und improvisatorischem Feuer lebt; um eine moderne und zukunftsgerichtete, in genauer Kenntnis der Tradition entstandene Musik. Scheinbare Gegensätze wie die von Intellekt und Emotion, Kontrolle und Überschwang: Hier sind sie aufgehoben.

Jochen Baldes und Franz Hellmüller, die das Projekt «Bloom-Effect» als Co-Leader gestalten und für die Kompositionen verantwortlich sind, kennen sich seit Jahren. In verschiedenen Konstellationen haben sie zusammengearbeitet, eine wochenlange Tour durch Sibirien hat sie zu Freunden fürs Leben gemacht. Sie jammen regelmässig locker in unterschiedlichen Konstellationen und tüfteln beharrlich an ihrer gemeinsamen Musik. Die meisten Stücke auf «The Way Out In» sind in einem dialogischen Prozess entstanden. Notenblätter wurden hin und her geschickt; manchmal enthielten sie weit gediehene Kompositionen, manchmal nur knappe Skizzen. Sie wurden bearbeitet, weiterentwickelt, verwandelt, vieles landete im Kübel. Bei den regelmässigen Proben brachten auch Sommer und Renold ihre Ideen ein; so entstand allmählich eine Musik, die bei aller Vielfalt aus einem Guss ist.

«The Way Out In» ist kein Konzeptalbum; gleichwohl ist es durchgestaltet und folgt einer schlüssigen Dramaturgie. Diese stand weitgehend fest, als die Band ins Studio ging. Die Stimmung war zugleich konzentriert und gelöst, Sommerferien standen vor der Tür.

«Herbstzeitlose», das zweite Stück auf dem Album, ist Baldes’ Lieblingsstück. Es berückt durch den langen Melodiebogen und durch Unisono-Passagen, in denen sich zeigt, wie traumwandlerisch sicher die Musiker agieren, selbst wenn sie ohne festes Metrum spielen. Das Stück offenbart den Zauber absteigender Linien und löst ein, was im scheinbar schlichten Titel verborgen ist: das Los der Herbstzeit und das Zeitlose im Vergänglichen. Um Vergänglichkeit geht es auch in «Noam»: Das Stück ist ein Triptychon, dessen elegisch-spirituelle Ecksätze einen lebhaften, weltzugewandten Mittelteil einschliessen. Es ist dem Andenken eines Lehrers von Hellmüller gewidmet, Noam Renen, der im Grossraum Zürich die Alexander-Technik vermittelte und 2019 in hohem Alter starb.

«Slider» ist die vertrackteste Komposition des Albums. Verschiedene rhythmische und harmonische Formen sind hier ineinander geschachtelt, die raschen Stimmungs- und Tempowechsel erinnern an Charles Mingus. Es scheint, als stellten die Musiker sich besonders schwierige Aufgaben, weil ein Lauf ohne Hindernisse für sie zu leicht wäre. In Baldes’ beschwingtem Solo purzeln die Ideen nur so übereinander, während Hellmüller in seinem Part elegische Schönheit entfaltet. Alle vier Musiker scheinen vollkommen unbeschwert zu spielen, doch hinter dieser Leichtigkeit steckt harte Arbeit. Die Musik wirkt rund, obwohl sie eigentlich aus lauter Ecken und Kanten besteht: Das Vieleck wird zum Kreis. Das könnte man auch von anderen Stücken sagen, etwa von «Sufi», das der Meditation indischer Mönche auf der Spur ist und einen kontemplativen Flow entwickelt, dem man sich gern ergibt.

Baldes spielt hier für einmal nicht Tenor-, sondern Sopransaxofon, ein Instrument, das er aber – ähnlich wie Wayne Shorter – nicht locker als Zweitinstrument behandelt, sondern mit besonderer Intensität spielt. Dieses Stück hat er Hazrat Inayat Khan gewidmet, dem Gründer des

Sufi-Ordens, und es zeugt nicht von andächtigem Pathos, sondern von der Verbindung von Spiritualität und feinem Humor. Ein Amalgam scheinbarer Paradoxien kann man, wie schon der Titel andeutet, auch im Titelstück «The Way Out In» erkennen, einem Stück, das die Dialektik von Abgeschiedenheit und Nähe gestaltet, wie Baldes und Hellmüller sie auf ihrer erwähnten Reise durch die sibirischen Wälder erlebten.

In der Schweiz bleiben wir dagegen mit dem Stück «LuLa», einem Kürzel für Luzern-Lausanne. Diese Bahnstrecke befuhr Hellmüller längere Zeit wöchentlich. Die Reise dokumentierte er in einer mehrteiligen, logbuchartigen Komposition. Dieses Stück wurde im Kollektiv dann aber stark bearbeitet, wobei das Bearbeiten vor allem im Weglassen bestand. An diesem Prozess der Verdichtung, der nicht nur «LuLa» betraf, mag es liegen, dass das Album einen sehr kompakten Eindruck macht – und Neugierde darauf weckt, wie das Quartett auf der Bühne mit dem Material verfahren wird.

Gut vorstellen kann man sich das beim Schlussstück des Albums, «Ambrosia». Es beruht auf einer Vorlage des Perkussionisten Dario Sisera, einer einfachen Melodie ohne Changes, die eine ideale Vorlage zum Improvisieren bietet. Dass das Stück im Titel die Speise der Götter in der griechischen Mythologie anführt, ist aber keineswegs ohne Bedeutung: «Trüge es nur eine Nummer oder einen anderen Titel», sagt Jochen Baldes, «würden bei mir nicht die gleichen Assoziationen das Spiel bestimmen. Wir wollen mit unseren Stücken Geschichten erzählen, unsere Titel sind im Idealfall Startrampen fürs Kopfkino.»

«Bloom-Effect»: Der Bandname leitet sich von den hellen Flecken her, die bei starker Belichtung von Bildern entstehen. Sie können einen blenden; sie können aber auch flirrende Intensität erzeugen und die Sinne öffnen für einen faszinierenden Sound-Kosmos.

Fazit: Dieses Album ist ein Glücksfall. Jochen Baldes und Franz Hellmüller als Co-Leader der Band «Bloom-Effect» schaffen die Quadratur des Kreises. Die Musik, die sie mit Patrick Sommer und Tony Renold eingespielt haben, ist gleichzeitig anspruchsvoll und unmittelbar sinnlich. Im Spannungsfeld von Form und Freiheit entfaltet sie sich. Als Teamplayer wie als virtuose Solisten spielen die Musiker Jazz von zeitloser Frische.

CD Linernotes Manfred Papst, NZZ am Sonntag

Circling the square

The raven eats pasta. Cheerfully, resolutely, oblivious to everything else around it. We see its jerky movements in our mind’s eye. Captivated, we enter the raven’s world, losing all sense of time. Afterward, we realize only eight-and-a-half minutes have gone by. What happened? We got lost in the magical music of Bloom Effect – specifically, the first cut on the quartet’s album The Way Out In. “Rabe isst Pasta” (The Raven Eats Pasta) – a title which would work well for a surrealist painting – captures the essence of the music in a nutshell.

Guitarist Franz Hellmüller and saxophonist Jochen Baldes spent a while bouncing ideas back and forth to come up with a series of compositions. They then took these into their rehearsal room, where they continued to develop them as part of their collective creative process. The result is a harmonious series of pieces, whose seeming effortlessness conceals its complexity. The sound of guitar and saxophone on the charming opening melody is so skillfully diffused it makes the listener wonder whether they are actually hearing multiple wind instruments. This carefully structured element gives way to improvised sections that follow the beats of classic modern jazz, in which Hellmüller and Baldes riff on odd time signatures like it’s the easiest thing in the world. Patrick Sommer on bass and Tony Renold on drums deliver much more than you’d expect of a vibrant rhythm section, with the subtle, poetic interplay between their two instruments elevating the soundscape to new levels.

Right from the very first track on The Way Out In the listener understands what this project is about: a hybrid form of jazz that blurs the boundaries between sophisticated composition and improvisational flair. It’s music which is modern and forward-looking, founded on a strong appreciation of what came before it. On this album, intellect and emotion, control and passion work in harmony, not in contradiction.

Jochen Baldes and Franz Hellmüller, the co-leaders of Bloom Effect and the minds behind the music, have known each other for years. Their paths had crossed on various projects before they eventually became friends for life during a tour of Siberia that lasted several weeks. They regularly jam with other musicians, but keep coming back to their own music to improve and refine it. Most of the tracks on The Way Out In came about through dialog between the twoartists. Sheet music got sent back and forth, sometimes containing fully-formed ideas, other times consisting of little more than sketches. They continued to work on these ideas – developing, changing, and, more often than not, discarding them. Regular rehearsal sessions meant Sommer and Renold were able to add their input as well, thus gradually producing music which, for all the diversity in its composition, is unmistakably the work of a close-knit group.

The Way Out In is not a concept album, though it does have a clear structure and coherent dramatic composition, both of which had been largely mapped out by the time the band went into the studio. With the summer break just around the corner, the mood in the studio was focused, yet relaxed.

“Herbstzeitlose” [Timeless Autumn], the second track on the album, is Baldes’s favorite, its enchanting extended melodic lines and wonderfully harmonious instrumental passages displaying a truly assured performance from the musicians, particularly given the rapid changes in tempo. This piece highlights the magic of descending melodies and reveals the theme behind the seemingly simple title: the inevitability of the fall season and its timeless transience. “Noam” is also about transience. A triptych, the spiritual, elegiac opening and closing movements of the piece bookend a brisk, world-embracing middle section. It is dedicated to one of Hellmüller’s teachers, Noam Renen, who taught the Alexander Technique in the Greater Zurich Area and died at an advanced age in 2019.

“Slider” is the most intricate composition on the album. Here, different rhythmic and harmonic forms overlap, the rapid changes in mood and tempo reminding the listener of Charles Mingus. It is as though the musicians deliberately added in a few exceptionally tricky passages, so it wouldn’t seem too simple. In Baldes’s ebullient solo, concepts come thick and fast, while Hellmüller’s part is an exercise in melancholic beauty. Though all four musicians appear to play effortlessly, this is something that only comes from a lot of hard work. Despite its sharp edges and many corners, the music feels well rounded. In other words: the square is circled. The same could also be said of other tracks on the album, such as “Sufi,” which is inspired by the meditation practices of Indian monks and evolves into a contemplative flow that is a joy to listen to.

On this track, Baldes switches his tenor saxophone for a soprano, an instrument to which he – like Wayne Shorter before him – gives due respect and plays with the intensity it deserves. Baldes dedicated this track to Hazrat Inayat Khan, the founder of the Sufi Order in the West.

Rather than devout pathos, though, “Sufi” is a celebration of spirituality and subtle humor. As the title suggests, the title track, “The Way Out In,” is a fusion of apparent paradoxes, a piece that shapes the dialectics of isolation and closeness – two states experienced by Baldes and Hellmüller as they journeyed through the forests of Siberia.

We then return to Switzerland with a piece titled “LuLa,” an abbreviation for the Lucerne-Lausanne rail link, which, for a long time, Hellmüller used to take once a week. He documented this journey in a multi-part, logbook-style composition. After presenting it to the group, they fundamentally changed the piece, primarily by cutting parts out. This process of consolidation may be the reason why the album as a whole, not just “LuLa,” has a very compact feel to it. It will be interesting to see how the quartet approaches the material on stage.

It’s easy to imagine how “Ambrosia”, the concluding track on the album, will be played. It is based on a musical pattern – a simple melody with no changes – by percussionist Dario Sisera, which offers the perfect backdrop against which to improvise. The track, whose title refers to the food of the gods in Greek mythology, was so named for a reason: “If it had a different title or just a number,” says Jochen Baldes, “I wouldn’t make the same associations when playing the track. When we play our pieces, we want to tell stories. Ideally, our titles should fuel the imagination.”

Bloom Effect: The band name comes from the bright spots that appear when photos are exposed to strong light. They can be blinding, but they can also create a shimmering intensity and open the senses to a captivating cosmos of sound.

Summary: This album is a godsend. As the co-leaders of the band Bloom Effect, Jochen Baldes and Franz Hellmüller have circled the square. The music, recorded together with Patrick Sommer and Tony Renold, is at once demanding and sensual, straddling the line between structure and freedom as it develops. This is jazz played by musicians – both as a unit and as solo virtuosos – that has a timeless yet modern vibe to it.

Musik als Roadmovie für Kopf, Herz, Beine und Seele. Musik die nicht mehr loslässt, zum Lachen und Staunen, zum sich Bewegen und Träumen.

Vier Musiker spannen einen musikalischen Bogen der Spannung und Entspannung, der Stille und Hektik, ein Bogen, welcher schönste Melodielinien und abrupte Brüche zulässt. Jeden Abend aufs Neue das Ungewohnte wagen und sich ohne Fallnetz auf eine Parforce Tour begeben – das ist die Kraft der Musik.

Das Publikum folgt gebannt dem Geschehen und ist freudvoll überrascht welche Wege die musikalische Reise nimmt – Destination unknown.

«Bloom- Effect» ist das Destillat aus Jochen Baldes‘, Franz Hellmüllers Tony Renolds und Patrick Sommers Schaffen bis Dato. Eine glückliche Fügung des Zusammenkommens vierer Ausnahmekönner, die ihre Kräfte bündeln und zusammen mit ihren Mitstreitern ungeahnte Bereiche der Musik betreten und diese lustvoll bearbeiten. Alle vier Musiker spielen seit Jahren in den verschiedensten Konstellationen zusammen und haben so eine musikalische Sprache entwickelt die blindes Vertrauen voraussetzt, musikalische Volten begünstigt und Freiheit im besten Sinne auf der Bühne erfahren lässt.

Music as a road movie for mind, body, and soul. Music that captivates, astonishes, makes you laugh, move, and dream. Four musicians span a musical arc of tension and relaxation, silence and agitation, an arc that allows most beautiful melodies as well as abrupt breaks. Venturing every evening into the unfa- miliar, to go on a tour de force without a safety net – that is the power of music.

The audience is captivated by the scene and pleasantly surprised by the twists and turns of the musical journey: Destination unknown.

Bloom Effect is the distillation of Jochen Baldes’, Franz Hellmüller’s, Tony Renolds’ and Patrick Sommer’s creative activity up until now. It is the lucky encounter of four exceptional artists who unite their strengths and, together with their brothers in arms, set foot in unknown territories of music and passionately work them. All four musicians have been playing together for years in various constellations and have so developed a musical language that presupposes absolute trust, encourages musical detours and lets true freedom be experienced on stage.

Review Jazzthetik 09.2021

This is the debut CD of an avant-garde jazz quartet out of Switzerland. According to the publicity sheet, “The essence of the group’s vision is to play a hybrid form of jazz that blurs the boundaries between sophisticated compositions and improvisational flair…modern and forward-looking music strongly connected with what went before.”

Of all the CDs I’ve received recently from Leo Records to consider for review, this is clearly the outstanding prize. One thing I immediately found interesting was that the opening number, The Raven Eats Pasta, uses a sort of stiffish, Stravinsky-like beat, surprisingly similar to the way Stan Kenton’s progressive jazz orchestra played in the 1940s. Kenton was crucified by jazz critics for this at the time, but he stubbornly stuck to his guns and created a loud but very exciting blend of pop hits, screaming brass and rich saxophone blends rooted by the baritone. In Bloom Effect, the sound of the group is rooted in Jochen Baldes’ tenor saxophone and the bass of Patrick Sommer. After the opening theme statement, however, drummer Tony Renold breaks up the beat by fractioning the time while guitarist Franz Hellmüller, who judging by the number of compositions bearing his name is the musical heart of the group, plays his solo. Thank goodness, he is a jazz guitarist and not a rock guitarist. (Sorry, folks, but too much of this whining rock crap just doesn’t belong in jazz, not even avant-garde jazz. Ornette Coleman took those elements about as far as one could go in modern jazz without making ot sound too much like a Heavy Metal band, and even he sometimes crossed the line for me.)

But make no mistake, all four musicians in this superb quartet are excellent improvisers. More importantly, they listen to one another; each solo builds on what has come previously, and somehow they make their solos complement the written portions of each score. Despite their adventurous harmony and rhythm, Bloom Effect thus manages to create whole pieces that have structure and form, yet still challenge the listener. The second number on this CD, Herbst- Zeit-Lose, is an excellent example, using an amorphous meter in the drums over which the other three musicians overlay a simple but effective lead line that tries to coalesce the beat into something more regular. The tension thus created between Renold’s very busy drums and the rest of the group is the heart of this piece; there’s very little improvisation going on here beyond the rhythm (except for a bit after the 4:30 mark), but there doesn’t have to be. Sometimes the composition is the message. This track reminded me very much of some of Coleman’s Sound Museum music.

In Noam the group gives us amorphous music using much more reverb effects than in the two previous tracks; indeed, this one is practically swimming in echo, which makes it more of a mood piece; but Bloom Effect doesn’t believe in soft, mushy jazz, so by the 1:20 mark we hear a loud crescendo, following which there is a bit of a rock beat, but thankfully more like the old jazz-rock of the middle ‘60s (think of Ramsey Lewis, Don Ellis or the Electric Flag) than like the heavy-metal crap of the 1970s and ‘80s. Curiously, I felt as if the melody that evolved here bore a slight resemblance to Barry Manilow’s Copacabana song, but then, suddenly, at the 3:50 mark the tempo really relaxes and we get a bass solo with little guitar fills from Hellmüller while Renold plays soft cymbal washes in the background, and the reverb has disappeared by now. This is almost a mini-suite or at least a tripartite piece built on almost classical lines.

But the best thing about Bloom Effect is that you can never tell what they’re going to play as you move from track to track. Every piece is different in mood, feeling and structure, yet one feels an odd sense of unity to the set as a whole. Perhaps they really do think of the sets they play as being sort of jazz suites; at least, that is the effect their music had on me as a listener. And as I say, despite all of the innovations one hears, their music is oddly pleasant. It has just enough of a retro feel to it to make it sound a bit more comfortable than the average avant-garde group, but also enough innovation to keep listeners on their toes. In Slider, it is the sudden shift of gears to a slow 3/4 at the four-minute mark, during which time Hellműller plays a wonderfully relaxed, almost genial guitar solo while the bass supports him and the drums go on their own merry way.

Sufi, described by Manfred Papst in the booklet as “a celebration of spirituality and subtle humor,” almost sounds like one of those 1970s pieces that one heard from bands like Return to Forever or some of the better cool jazz musicians of the late 1980s. Baldes switches to soprano sax on this one, but plays it with a full, rich tone that almost makes it sound like an alto. (Perhaps it is, but if so it is played for the most part very high up in its range.) At about the six- minute mark we suddenly dip back into reverb as bassist Sommer plays an excellent bowed solo while the guitar slides around on the upper ranges of its strings. This is extraordinary meditative music.

The remaining tracks explore other little avenues and alleys on the jazz path, such as The way out in with its asymmetric meter, constantly shifting as the melody wends its way along, the texture thinning out to another bass-drum duo with soft little guitar fills, eventually leading to a guitar solo accompanied by bass and drums. And everything coalesces, with a slight increase in tempo, when the tenor sax moves in for the final chorus. Lu-La is another ambient piece with reverb; oddly enough, this piece was written in tribute to the Lucerne-Lausanne railroad link. You’d never guess it…until it suddenly breaks out into a funky dance beat at the 5:30 mark!

The best thing I can say about this album, and I really mean this, is that I could listen to Bloom Effect all day and never get bored, annoyed, or tired of them. Their music is challenging and relaxing at the same time; they’ve mastered the art of pushing the envelope while still creating balance and structure. Nothing sounds trite just as nothing sounds as if it were just being done for shock effect.

These are MUSICIANS, and excellent ones at that, creating musical meditative states for the mind.

—© 2021 Lynn René Bayley THE ART MUSIC LOUNGE

Jazzfestival Kursk after the Gig

Takt TV: http://takt-tv.ru/index.php/takt-novosti/5119-dzhazovyj-udar

Interview Morning TV Gubernia: http://tv-gubernia.ru/programmy/efirnye_programmy/den_vmeste/den_vmeste_1112016/